I’ve found there are some problems with art.

“Really” you say.

“Have you figured out the solutions?”

I think I might have.

“Well you better tell us then.”

Okay then.

“Jolly Good.”

When I was a child I was confused as to why my teachers didn’t seem to realise that art was a mechanical process.

I wanted to draw a good picture in exactly the same way that I wanted to get my sums right, but for some reason the teachers would see a barrier between the two.

Maths and art. One involves the composition and arrangement of abstract concepts, and the other one is art.

The difference between the two is that a teacher is allowed to tell a kid when his sums are wrong, but not when his drawing is.

This is not the case with all artistic pursuits.

When you learn an instrument the teacher tells you the correct way to hold it, the correct way to play a note, and the correct way to play a piece.

For some reason the teacher doesn’t hand a violin to a child and tell them to try and disregard all concepts of the correct way to play music, to look beyond the notion of “notes” and “pieces” so as to approach true creativity.

This doesn’t happen because the child would start whacking the violin on the table. However, if they perform this action with a paintbrush in hand it is recognised as the correct way to develop artistic skills.

Children aren’t fooled. They know when someone stinks at drawing and they’ll let them know about it. The teacher recognises this development of an aptitude hierarchy as being detrimental to the spirit of education, and reprimands the child for reprimanding another child’s work.

Having completed this duty to the arts they will then give each of the students a number out of 100 for their abilities in math, science, music, reading and writing.

Is there a difference between drawing and writing?

If you tell a child that they could be better at writing, will they be so discouraged that they'll never write another word?

The problem is that adults have been trained to look at the work of a child and think,

“This looks kind of like a Picasso, and I don’t know why, but apparently that’s the highest form of art.”

Consequently they end up praising children for making drawings that look like the work of a child.

This can be really annoying for the kid who is desperately trying to draw something that looks real.

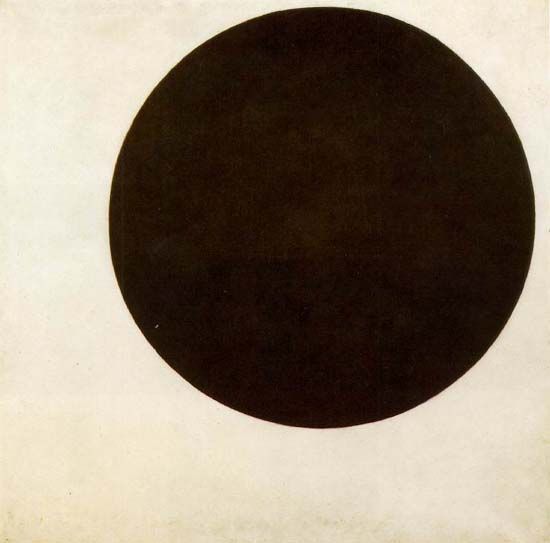

The last thing a child wants to see is a drawing that looks like the work of a child, and the last thing I want to see is another artist who reaches the skill-level of an infant before believing themselves to have achieved perfection.

Teachers don't look at the writing of a child and say,

"I see you've decided to remove all punctuation and capitalisation to create a "Stream-of-conciousness"style approach which has obviously been influenced by the work of Kerouac! You must be a genius!"

Instead they say "This is a semicolan; here's how you use it."

Understanding punctuation isn't going to inhibit the child's ability to write expressively.

It all seems a little bit strange to me.

If a school can see no value in developing the drawing skills of a child, then I can understand that. I’m not going to argue that the ability to draw is of any value in society.

But if they are going to set aside time to teach art, why don’t they try doing some teaching?

They don’t hand a book to a child and tell them to develop their own, unique approach to reading the symbols, so why do they feel so unqualified to designate a correct approach to art?

About a hundred years ago it became popular for practitioners of the arts to start subverting the foundational principals of their practice, but it’s only in the field of visual arts that we forgot to tell them to shut up when it became boring.

Why?

Probably because it was the only field of art that didn’t have a good enough reason for existing in the first place, but I won’t try to prove that here.

The point is that decades after artists all got together and decided to try only talking about themselves for a change, their anti-hypothesis hypotheses have only become popular in the field of visual arts.

This is a problem.

Either all arts are crap, or the artists who tell you that all arts are crap, are, in fact, crap.

So the answer is to stop being so afraid to actually teach children art.

It’s not all that different to teaching them to write:

First you become acquainted with the language, then the symbols used to communicate the language, then the ideas that the language communicates through the symbols. Done.

If that didn’t sound like a complete pile of balls you should stay tuned for the next post which will talk about the problems involved in bringing children into contact with the history of art.