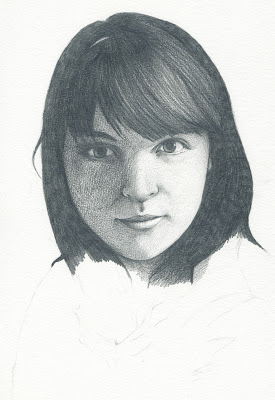

But I recently took a weekend off to make this drawing:

The process of making a drawing can seem very simple, but in

reality there can be a lot of trickery behind the magic. To illustrate this I took a series of scans

of the drawing as it was being developed.

So what is the big secret?

The short answer is; there’s a photo in there.

I can understand that this might seem like cheating, but I

hope I can make an argument that this is art in its purest form.

First I’ll show you exactly how the drawing was made, then I’ll

talk about how tricks and technology have been a driving force behind the

development of art.

How to draw like a machine:

You have to be accurate.

Ridiculously, unbelievably accurate.

First up, I took a photo of Clare (took about 70 actually, and

then selected one), I put it into photoshop, cropped it, and resized the image

to match the physical dimensions of my paper.

Next I put a grid of guides over the face and other critical

areas, and ruled up the exact same grid onto the paper.

From here I used the grid as a reference for outlining all

of the features of the drawing.

Then I carefully erased the grid, leaving the line drawing

as the new reference.

Each of these work-in-progress scans was overlayed onto the

photo in photoshop in order to find out what was slightly off. Throughout these first few images I was correcting

the placement of a lot of these lines by as little as half a millimetre.

It might be just me, but I always find it hard to progress

past the perfection of this blanched-white phase in a drawing. It always seems like each step from here just

increases the murkiness.

From here on out it was a long process of filling in the

drawing, and scanning to measure the accuracy of the overlay.

It’s important to try to and achieve the darkest you plan to

go, early on in the drawing, in order to give you a good frame of reference for

all of the tones.

The following set of images are just a matter of patiently

translating the tones on the screen to the blocked-out image on the paper.

At this point the drawing stage is essentially over, but it

still looks nothing like the finished product.

This is because the image above is a scan without any editing.

Every drawing that you view on a screen requires digital editing,

even for the purpose of creating an image that actually looks like its

hard-copy counterpart.

This particular drawing required a lot of editing, the

details of which are quite technical, but I’ll try to briefly summarise the

steps in a paragraph. Feel free to skip

to the next bit.

The drawing has to be perfectly aligned over the photo, then

I use an adjustment layer for Levels (try to be as subtle as possible with

this). Next I use adjustment layers to

almost entirely desaturate the original photo (still keeping some colour), and

amp up the contrast with levels (can be less subtle here as it is all about

showing through the drawing). I took the

drawing’s opacity down to about 55%, which is a fair bit lower than any other

time I’ve made something like this, but I felt it was at the cusp of where I

personally could notice the combination.

Then I made several layers of varying opacities directly below the

drawing where I painted in a lot of blacks and some whites, in order to even

out the tones, and to get more drawing texture around the edges and less around

the centre.

This is the image I finished up with:

I could have made the photographic element much more subtle,

but I wanted to push it to the point of blurring the line between tradition and

digital media.

Incidentally, this is an example of one of my drawings with

a much more subtle photographic presence:

Now we come to the question: Is this still a drawing? Isn't it cheating by relying so heavily on a photo?

This is not something I considered at all until after

the drawing was complete, when it occurred to me that the image could appear as

though it’s claiming to be nothing but pencil and paper.

As to whether this is morally justified I include, for

anyone interested, my own opinions below.

The evolution of Western art has been closely tied to

technological advancement. The development

of new art materials is one aspect that has consistently opened the door to new

possibilities.

The pigments of colours, for one example, all originally came

from different places; blue from ground up rocks, purple from sea-snail shells,

and so on.

When Turner or Van Gogh used the newly developed Viridian

Green (created from a chromium oxide dehydrate)

in order to get a richer saturation of green, I don’t think anyone would

describe this as cheating.

Technology has also contributed to artistic processes.

This woodblock print by Albrecht Durer (1471-1528) shows

almost the exact same grid process that I used to map out my drawing.

Another example by Durer has the subject of a picture described

as a series of points where a length of string intersects with a screen.

Clearly Durer did not feel that these methods should

conflict with the purism of drawing. The

point of artistic process is to reach the endpoint of the artwork. Durer used any available technology to

improve his work, and is recognised as one of the greatest artists of his era.

A few centuries later Vermeer (1632 – 1675) was painting

pictures like this:

It is now theorised that Vermeer used the newly developed

glass lens to create a camera-obscura effect to project an image onto a canvas

where he could very accurately trace the picture and develop it into a painting.

The point is that Durer and Vermeer are not great artists despite incorporated technology into

their practice, they’re great because of this.

It comes down to how you define the role of the artist. I personally feel that the point of an image

is to affect someone, based as completely as possible on the content of that

image. I would prefer to like a painting

because of how it affects me, rather than because I know that it’s famous or

expensive.

This gap is magnified in examples of books which are

apparently autobiographical, but turn out to be fiction. People tend to feel that they were lied to,

but I feel that the point of the book was to get people to feel like they

experienced something.

Nowhere in Oliver Twist does it explicitly state that the

story is not a true account of actual events. Stories are basically all lies,

designed to trick you into feeling something.

There’s no point complaining when the illusion becomes too

convincing. Its job is to be convincing.

As an artist my job is to trick people into enjoying the

visual experience of an image. Often

this involves creating the illusion of a three-dimensions where only two exist. Sometimes there can be tricks that play on

the idea labour.

Most visual art is largely about novelty, and one of the

most basic ways to be novel is to have put a lot of labour into

something. Labour has always been

greatly valued in visual art, but not necessarily for reasons that are

consistent with the function of art.

When James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834 – 1903) pioneered

the abstraction of painting in his “Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling

Rocket”:

He ended up being forced to argue the validity of his work

in court, from which the following exchange was transcribed:

Holker: "Did it take you much time to paint the

Nocturne in Black and Gold? How soon did you knock it off?"

Whistler: "Oh, I 'knock one off' possibly in a couple

of days – one day to do the work and another to finish it..." [the

painting measures 24 3/4 x 18 3/8 inches]

Holker: "The labour of two days is that for which you

ask two hundred guineas?"

Whistler: "No, I ask it for the knowledge I have gained

in the work of a lifetime."

(This last quote by Whistler I often see wrongfully attributed

to Picasso)

In my own picture it’s true that it would’ve taken a lot

more time and effort to achieve the level of detail evident without

incorporating the photo. But creating a free-hand drawing accurate enough to

seamlessly overlay onto a photo is exceedingly difficult.

In the 20 or so years I’ve been drawing, this

is the first time I’ve been able to achieve this effect properly. I’m certain I could’ve drawn an equally

effective drawing without involving a photo, given a larger (and much smoother) piece of paper, but it

would’ve taken me several more days of work, for a similar end result. Knowing where to cut corners is essential to

being proficient in any field.

As Whistler argues above, judging an artwork based on the

time spent working on the project fails to take into account the lifetime of

skill and knowledge that can enrich that time. Furthermore, when experiencing something has

real value, the duration of time spent in its production becomes fairly

arbitrary.

When I’m watching, reading, or listening to something

amazing I don’t tend to be pondering the finer details of production.

And finally, if this set of reasons is ultimately

unconvincing, my position is and has always been that:

As a note to anyone who actually knows a lot about the history of art (I'm looking at you, Liz), the above claims were made from memory and whilst probably factual are subject to varying degrees of minor inaccuracy.